Anthology Poet Highlight 36/82: Sara Blaisdell, “Ophelia“ (This links to an earlier version of the poem.)

[audio:http://fireinthepasture.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Blaisdell_Ophelia.mp3](My reading of “Ophelia” [the anthologized version])

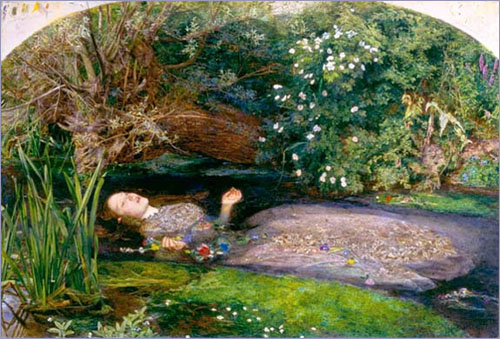

Sara’s “Ophelia” makes me a bit melancholy. As does the painting upon which I’m pretty sure it’s based (see above). As does Shakespeare’s lady “of ladies most deject and wretched, / That suck’d the honey of [Hamlet’s] music vows” and who, after falling in love with then being rejected by that “prick prince,” made her way into Shakespeare’s brook, “dead men’s fingers” wrapped around her neck; then into John Everett Millais’ remix; then into the poet’s purview and onto the poet’s “wall” (if the speaker in “Ophelia” can be trusted, anyway). It’s uncanny, really, this layering of Ophelia’s image: supporting dramatic character become subject of a Pre-Raphaelite obsession become mass-produced art print become lyric rumination on, among other things, art, the human condition, life after death—and the potential intersections thereof.

Speaking somewhat to the ways such reproductive layering widens the gap between the creation and reception of an artwork, Walter Benjamin—literary critic, philosopher, intellectual—wrote in 1936 that “that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art. This is a symptomatic process whose significance points beyond the realm of art” into broader cultural and natural landscapes, a process that speaks to the modern world’s drifting away from contact with that which is authentic and original. Benjamin continues, “One might generalize by saying: the technique of reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the domain of tradition.” In other words, the act of reproducing, say, a painting or even, to back a step further toward Creation herself, a panoramic landscape or a human body (as portrayed in a painting or a photograph or film), puts distance between the original and its audience. Such distancing, as Benjamin has it, diffuses the aura of the work, weakening its aesthetic impact, suppressing what aesthetic power and authority the original may bear by virtue of its having been touched and cared for by the creator and thus infused with something of the creator’s life force.

But this life force doesn’t exactly disappear. In fact, it may be that some of the original’s aesthetic, cultural, and psychological DNA gets passed to each remixed, mass-produced, and mass-distributed copy spawned through the reproductive process. In this way, something of the parent work’s “genetics” flow into and through its “offspring,” whose presence and countenance double for the aura of the parent and enter different cultures and traditions. Of course, they’re not the parent’s aura. But, to return to my point of departure, the doubling effect inherent in the relationship among each displaced copy and between each copy and the original is uncanny—each repetition of or variation on the image may arouse in viewers a sense of familiarity with the image’s aura: the copies look and feel a bit like the original. Yet, because the image has been decontextualized and re-purposed, it also becomes unfamiliar: although the copies may look and even in cases feel like the original artwork, they’re not the original; they’re copies. Any aura they bear is imitative and thus inauthentic.

But that doesn’t make their aura or their influence any less real or affective. Consider, for instance, the case of Sara’s “Ophelia”: she’s written a poem addressed to a character in a painting based on a character in a play. And while poem, painting, and play are each separated from the others by centuries, cultures, and artistic genres, the pathos they share is at once cumulative and reiterative: poem comments on painting comments on play, which in turn adds aesthetic, cultural, emotional, and psychological value to the painting, which in turn adds aesthetic, cultural, emotional, and psychological value to the poem. And so on.

From the title, then, “Ophelia” comes drenched in associations: Associations between the wry poet and the intended recipient of her cynicism, which bitterness may turn out to be, as the speaker claims, just a symptom of the poet’s “jealous[y].” Associations between the poem and the “crowd[ed]” canon behind it: the mass-produced art print the poet purchased for “6.95 / at an art sale,” the Millais painting the print imitates, the life and death of Shakespeare’s supporting lady, even Christianity. Associations between this canon and the reader at least acquainted enough with its tragic tale to catch the allusive pathos of the poem’s subject and its potential to touch “everyone” who has felt the pangs of life in a fallen world, of unreciprocated love. Who has death hanging over them like a cheap art print hung in “every room of the house.” Who could find in that print—that lowly reproduction of Millais, which is really just a fictive reproduction of another fictive reproduction of flesh-and-blood humanity—a melancholy hope that even after death we “keep floating,” we keep thinking, singing, reaching out for “something” (maybe what we, as Ophelia, “think [we] deserve”: to be remembered) until we at last rise in “the resurrection,” which is ultimate proof that, like Ophelia, even though we may give up on ourselves and on each other, Christ never did and never will.

John Everett Millais' Ophelia at www.tate.org.uk

John Everett Millais' Ophelia at www.tate.org.uk